The Rogue Patient

This is the first in a series of posts helping people navigate hard medical conditions.

In this essay series I’ll describes a set of common causes in the form of biases, assumptions, actions underlying sub-optimal health outcomes that I’ve seen first-hand, heard about directly from others, or understood through reading the primary literature. I’ll start with my own story in this first essay.

San Francisco, 2018.

Doctor: Ari, please sit down. We got your scan images back. It’s not good news. Unfortunately these results are consistent with Non-hodgkin’s Lymphoma. I know this isn’t what you were hoping to hear and I’m sure you have a lot of questions.

Me: (stunned, the blood flushing from my head) …I… don’t think I understand…uh, what does this mean? How bad is this?

Doctor: An Oncologist will follow up shortly with more information. For now I’d probably avoid searching things on Google.

I searched Google. The doc was right, I wish I hadn’t.

The Oncologists plan: inject me with poison to kill it faster than it can kill me. This is as counter-intuitive as it is rational and necessary.

Chemo treatment

I look at the plastic tube in my forearm. I suddenly feel gravity pull me into the plush leather chair. The irony of poisoning myself in comfort. It all hinges on this protocol, messy medical statistics and the promise of atomic interactions; a toddler corralling wild animals. Should the plan fail, my personal cosmos dies: no more kids: Saul’s tender locks, Lev’s joyous screeches, Lua embracing my leg as I limp up stairs like Capt. Ahab, Michelle’s sweet voice calling ‘Ari’. No more grand ideas, great food, smelling warm homes, whiteboard sessions with my team, crisp air on my cheek. Sunday walks in a garden disappear, along with electric purple flowers. No more hypnotically staring at golden dust diffusing in a ray of sunlight. Game over, and a wake of hardship/sorrow for my family and friends. Ugh! I squeeze all of… this.. into my palm in vain attempts to strangle something.

I look up, noting the machines on stands, IV drips, beeping things and sterile walls. My eyes drift to the floor. Black nurse clogs step into my teary peripheral vision, then back away tactfully. I clench my eyes and inhale, gagging on the smell of glue molecules. Why does that stretchy corrugated tape smell like that?

I lift my eyes to hers. Let’s do it.

The Nurse hooks up the Rituximab to the orphaned end of the tubing. I pick up the hastily stapled sheet she printed out at my request. The second line reads - in 94 font - “SIDE EFFECTS CAN INCLUDE DEATH…”. Pointless, I think. I put it down. Try to relax.

End of Chemo treatment

After completing 6 rounds of chemotherapy, the so-called “first line of treatment”, I completed a CT scan. The purpose was to tell the doctors whether the treatment had killed the cancer. The way to understand this type of cancer is in likening it to a house fire; 90% extinguished is not good enough.

Oncologist: Ari, sit down. Bad news. Your scan came back positive. This means There’s still activity. The treatment was not fully successful…Followed by a set of words, by which time my mind was elsewhere entirely.

The recommendation: more intensive chemo, followed by a stem cell transplant. Terrifying would not do justice to that conversation, probably the hardest of my life. I literally dropped my phone on the concrete, smashing the face. This was much worse than the initial diagnosis. This time I was anticipating the call, I knew what this meant.

The road not taken

Navigating a hard medical condition is a war on multiple fronts, spanning biology to the healthcare system. The key to achieving an optimal medical outcome (whatever that means for a given situation) is intelligent and active patient engagement. Said another way, a great way to achieve suboptimal medical outcomes is to listen to your doctor, unblinking and unquestioning.

But what had become apparent over the preceding months was that our collective medical knowledge does not extend very far; consider that bloodletting as a cure-all treatment only ended in the late 1800s. Each time I would ask a few questions I’d find myself at the edge of human knowledge. That’s not an encouraging place to be.

I resolved to be fully involved in every detail of my treatment. To cut a very long story short, I took a highly proactive role in navigating the experience. Below is a sampling of procedures and treatments recommended by my docs that I was able to modify or avoid entirely during my journey:

Avoided an unnecessary stem-cell transplant which would have included living away from my wife and 3 kids for months, while living in a bubble. Not to mention the damage my body would have absorbed.

Avoided intense follow-up chemotherapy treatments with low odds of success.

Decided to enter an experimental and dangerous clinical trial (in the end it was unnecessary).

Altered a surgical procedure that would have sliced me open like a gutted fish and immobilized me for 6 weeks.

I should say none of this has to do with medical malice, incompetence or the like. Instead, this speaks to the potent mix of challenges related to treating people at scale for things for which the mechanisms aren’t well understood.

For the better part of a year I found myself navigating the most complex set of decisions I ever had to think through. I had to do this while in an emotionally charged state. It was psychologically taxing. Not only because of the logical depth, but also owing to the emotional intensity. For example I’d read through white papers about my condition and new research paths to treating it then discuss with researchers in the field. But later in the same day I’d slip into an introspective mode, pondering mortality while staring at a sink full of sippy cups.

Sitting in a chemotherapy chair is, strangely, like being on a bus. It’s not so much that the seats aren’t comfortable (they are), the passengers rude (most people are kind), or the smells unpleasant (that depends). Rather, it’s a place - increasingly rare in society - in which a representative cross-section of society can be found in the same room. Not only that but with a common set of goals - to survive, sometimes against massive odds. I’ve had the opportunity to talk to my fellow travelers. I heard their stories. And gotten to learn about how they engage the system.

What I learned is that achieving the best outcomes is not about having the best doctor or being in the fanciest system. That definitely helps. But the variance in outcomes is just as much a story about how people engage (or don’t) with the healthcare system itself. This is based on my experience as a patient, but it isn’t only my story. These stories happen every day to people navigating the medical system.

This all has a happy ending, in my case I am in complete remission. I was able to minimize damage from procedures, and entirely avoid some very intense treatments. This spared my body massive damage, but more importantly reduced the suffering my family needed to bear watching me go through all this.

How was I able to navigate an otherwise terminal cancer diagnosis and avoid unnecessary treatments and procedures recommended by some of the world’s best oncologists? This essay will equip and empower patients (or their loved ones) with a set of tools to successfully navigate a hard medical situation. My hope is you emerge on the other side with the best possible outcome, whatever that looks like for you.

Principles for navigating hard medical conditions

Below are a set of principles to help you navigate the system successfully. My hope is these practices will help set you on a path to achieving the outcomes that matter, whatever those may look like in your particular situation.

1/ Prepare: Define your people/community

The first thing you might consider doing is sending a note to all the people you love. The reason for this is scalability; one message to your full network instead of one-offs. The additional benefit, beyond time savings, is that you may be surprised that people will use this to further spread the message for you to people you may have missed. In my case the email was used as part of a go-fund me that my friends setup on my behalf, without my knowledge. This email was an asset they could use.

Here’s the letter I sent to everyone in hopes this may serve as a template for you.

Consider the support you think you’ll need. Get those people involved as soon as you can. They want to help and need to know what’s going on. This is no time for pride or shame to get in the way.

2/ Understand: big medical decisions are one-way doors

How much uncertainty is tolerable when making a life and death decision? I really like what Jeff Bezos says in one of his annual letters about one-way versus two way doors: 2-way doors ought to be made with a bias towards speed over perfection (you can always go back or iterate the decision). One-way doors in contrast are non-reversible and ought to be made with great care and deliberation.

As with any decision there is a key distinction to be made between the decision itself and the outcome: sound decisions can turn out badly, poor decisions sometimes work out well. But lucky outcomes over time tend to favor the better decisioning process (again, any single decision may not). So the mental framework I used is to squeeze all my information gathering into a specific time window.

Here’s the algorithm:

Timebox the decision

Gather as much relevant information inside of the time window

Synthesize the learnings

Decide and gut-check (regret minimization)

Act

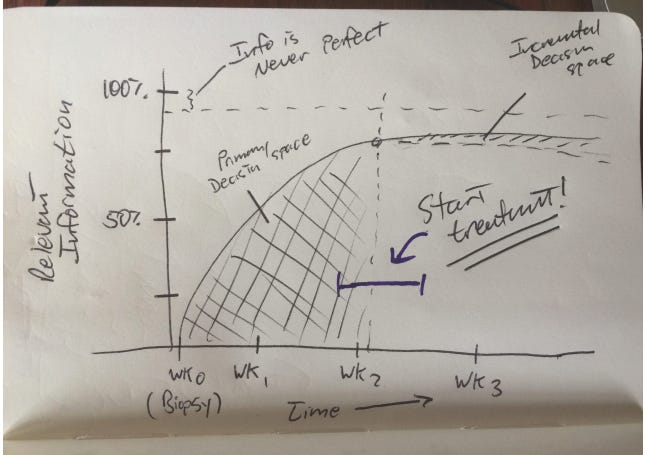

This was the napkin chart I had drawn at the time to illustrate the approach I would take. Below is a schematic I had drawn for myself during treatment. On the Y-axis is relevant information to gather, vs. time on the x-axis. There is no perfect information and much that will never be known. The majority of the relevant information must be gathered within 2 weeks (the big shaded area), with incremental utility coming after that (small shaded area).

3/ Ask the most important question

At one point I was evaluating my options which included a stem-cell transplant, versus a clinical trial for an experimental new drug (called Car-T). I had little basis for making this decision as I was no expert in the particular domain. The approach I took was to make a list of my smartest friends. These were people used to making decisions with a lot of uncertainty. They included CEOs, startup founders, company executives, scientists and the like.

The approach I took was simple. But hard. I gave them the scenario I found myself in as clearly and succinctly as possible. And then I asked one simple question: if you were me in this situation, how would you think about this?

What fascinated me about the result, was that it only took 4-6 such conversations to reveal a pattern. In my case the need for quick answers/speed was the most important thing. Once I had 4 of these people tell me the same thing - you need an answer as quickly as possible - then I felt clear on this approach. Note the key point was that they had no specific domain knowledge and yet all aligned on the same approach!

Sometimes the best answers don’t come from the experts, but rather from smart generalists.

4/ Balance reason with emotion

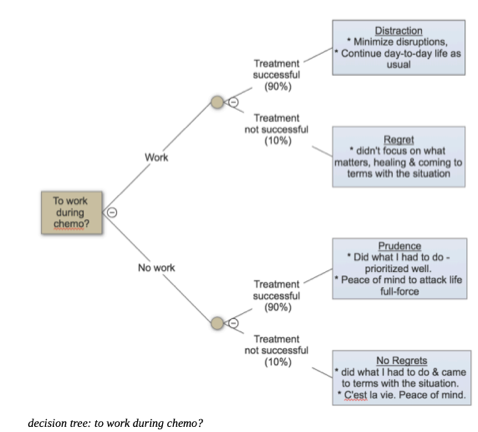

When I first was diagnosed with Cancer I had to make a few decisions. Among the more practical was whether I’d work during treatment. I considered both the probabilities related to outcomes, along with my emotional state. In particular I focused on regret minimization. After all, we only have one life, and probabilities will only get us so far; unlucky bounces will happen!

Making emotional decisions is a recipe for making bad decisions. I’ve concluded that when it comes to healthcare decisions, it’s best to think in 2 distinct modes: Rational first, then emotional.

I think of the purely rational version as entering Spock mode (from the Star Trek series). What would Spock do? But then I’d balance this with my gut, intuitions. Always gut-check decisions. Hurl yourself into the future, looking back to this moment from a future in which things don’t work out in your favor. If the gut disagreed with my logic I would dig in again to understand the tension.

Below is an example decision tree I put together to figure out whether I should work during Chemotherapy. While the odds are the same, one branch contains regret whereas the other does not. For that reason I decided not to work during treatment. I could not live with the “regret” scenario in which I worked and treatment failed.

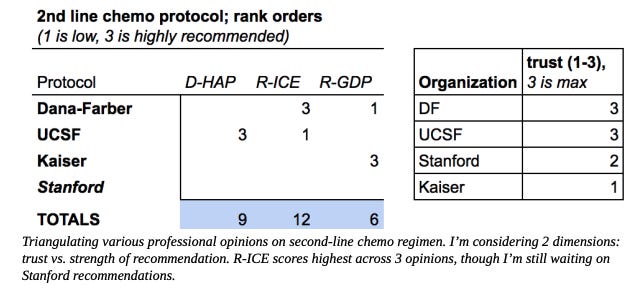

5/ You’re the CEO of your healthcare

After completing 6 rounds of chemo I learned that the treatment had failed. I was faced with a dizzying array of so-called second line treatments. These took the form of different cocktails of chemotherapy drugs being recommended by different institutions. There was no specific recommendation and I was to decide! Each had its pros and cons, including the ambiguity of who was reporting on them. Below is the quick chart I had put together to make sense of my decision. A key point in assessing any option - especially if one isn’t an expert in the domain - is to factor and weight trust explicitly if you can. For example in the model below I balanced protocol recommendations with how much I trusted the recommending Oncologist.

6/ Convert hard things into events

For each of the 6 rounds of chemo treatment I created a strange party. I’d personally text my friends or colleagues that I thought might be interested in joining me. I would benefit from their support. But a funny thing happened, I realized this was actually meaningful for them as well. They wanted to join me! Instead of spinning in my head while suffering through this hardship, these ended up becoming parties of a sort. That was truly unexpected. And it wrapped the whole thing in a warm blanket of meaning. When I reflect on my chemotherapy sessions I actually have great memories, connecting deeply with my friends on everything from the mundane to the dark humor (ah, I don’t remember that email, I’ll go back and find it when the doctor confirms that I have a few minutes…remaining).

See if you might be able invert your suffering, turning it into joy.

Where do we go from here?

This is the first in a set of essays on navigating hard medical conditions with a focus on the US healthcare system. Subscribe to get future posts delivered to your inbox.

Ari, this post is saturated with wisdom: clear analysis coupled with honesty born from lived experience. Thanks for sharing. As someone coming from the healthcare side of things, I appreciate the way you give very practical "how-to's" to others who may find themselves staggering through a dizzying system. I'm slowly catching up and am looking forward to reading more.

Wow. There are so many ways I could react to this-- as a writer (the imagery and the stories you share are so vivid and new; the "electric purple flowers", the chemo room being a "cross-section of society", that flow chart of life and death-- are images that I can feel getting stuck in my head for the next few days), as someone working in healthcare (often being on the other side of the conversations you mention, I have to admit "Each time I would ask a few questions I’d find myself at the edge of human knowledge." is so real), and as a fellow human with a chronic health condition (and knowing the advice many therapists/medical professionals give are template answers you've heard before which you know won't work for you).

I suppose that's vested interests x 3. Jumping on board!